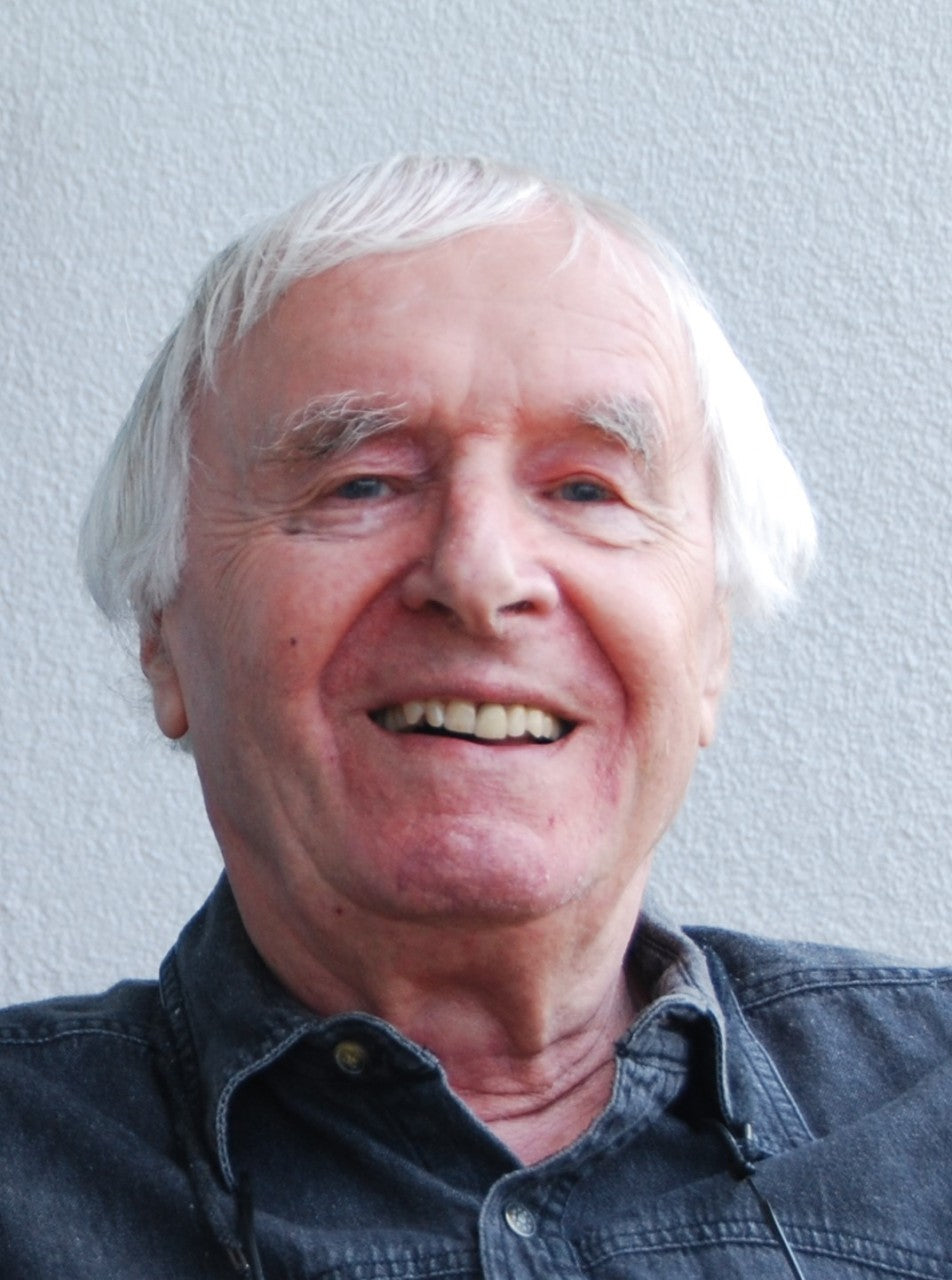

From ambitious missionary to disillusioned church critic: Interview with Bernward Mankau

From ambitious missionary to disillusioned church critic: Interview with Bernward Mankau

"Since my youth I wanted to go into mission, in the conviction that the Christian faith must be carried out into the world. But in Congo I experienced a church that was only concerned with power and maintaining power and that was not afraid to collaborate with repressive governments." After his experiences in the African mission, Bernward Mankau , author of the book "Blind Flight" published by Herder Verlag, has been reduced to lay status. In his opinion, the Christian church must return to the foundations of its teachings in order to avoid losing further credibility and believers.

In your book “Blind Flight” you describe your time as a missionary in the Congo. What motivated you to embark on this adventure and how did you prepare for it?

Mankau: It was a long time of preparation. Growing up in a very Catholic family in the diaspora, where Catholics still had to distance themselves from others, it was my wish to become a priest and a missionary. My involvement with the Boy Scouts contributed to this. From the very beginning, I wanted to go into mission because I was convinced that faith had to be carried out into the world.

When you came to Africa in the mid-1960s, many of the countries there were undergoing a transformation in order to break away from the former colonial powers. How did you experience the political situation at that time, and what is left of it today?

Mankau: When I came to Congo, the former colonies were in the process of separating from the European powers. But the borders drawn by the colonial rulers in the 19th century, sometimes with a ruler and without any consideration for the peoples living there, remained taboo. These borders were only questioned during the Biafra War. The new masters of Africa did not touch the borders of the colonial empire, including the former Belgian Congo.

In addition to being a pastor and secretary to the Bishop of Kenge, your main role was as a bush pilot, delivering food, medical aid, etc. to an area the size of the Netherlands. How did you come to this role and what impact has it had on your faith work?

Mankau: I was a passionate pilot, not a professional pilot, but I was also a missionary with the same enthusiasm. I learned to fly in Germany. In the Congo, however, I had to initially adjust to very unfamiliar conditions, such as navigating the many small, self-built airfields without any help or instructions. That's why the actual missionary work initially took a back seat.

After independence, the Catholic missionaries continued to guarantee a school system, but at the same time stabilized the authoritarian system of the then dictator. In your opinion, what role did the church play in colonialism, and what were its shortcomings and achievements?

Mankau: The Church on the Congo was one of the strongest forces in the country during the colonial period, not only because of its well-developed school system, but also in the social sphere. It worked closely with the Belgian colonial government. Today, we would probably call this a win-win situation. The Church tried to maintain this influence after independence. This went relatively smoothly in the West of Congo, but things took a dramatic turn in the East. Many collaborators of the hated colonialists were killed here, including numerous church representatives. The Church has always failed, or even refused, to defend itself against the selfish, nationalistic or antisocial machinations of the state. The Church remained true to its own traditions, competed with other Christian churches and caused insecurity among the locals. Even the traditional ancestor worship, which exists among many peoples of the world, sets God aside, the local vicar general accused me when I paid my last respects to a dead friend and poured palm wine, which he had drunk so often with me, on his grave in the savannah. Placide Tempels, a Belgian missionary, wrote in his "Bantu Philosophy" during the colonial period that it was something like intellectual suicide for the African to have to give up his tradition.

You see the constant exodus from rural areas as the main problem of Africa's ever-growing urban centers and the root of the large refugee movements to Europe. How can these causes of flight be combated and what tasks can the Christian mission fulfill in this regard?

Mankau: I don't know whether the Christian mission can really help here. It can try to slow down the rural exodus and - like the monks of the Middle Ages did - keep people in the countryside by helping them to establish a regular agricultural economy and by setting an example. However, I believe that the exodus towards Europe can only be stopped if everyone has a job and an income.

Your own experiences and many conversations with missionaries who were initially highly motivated and became increasingly disillusioned have made you a sharp critic of a conservative and opportunistic church. What do you accuse it of and what might be a solution?

Mankau: The criticism of the church, which is based on many conversations with missionaries of the same age 50 years ago, often referred to the Second Vatican Council, which promised us a new beginning that we had been waiting for but which did not happen. The solution to the church's current problems could be for it to return to the foundations of its own teachings and live by them. And these principles are best formulated in the Sermon on the Mount. But as long as it is only about power or maintaining power, these wishes are not feasible in my opinion. And the church will continue to lose credibility.

After the personally valuable and formative years in Africa, you left the missionary order that had led you on this path in 1972. How did the rest of your life go and what did you take from this time for the future?

Mankau: I left Congo at Christmas 1971, and the following year I was relegated to the so-called lay status. After a short time at a Munich school, I was head of the Murnau Education Center for almost 30 years, where almost four hundred asylum seekers from many countries, German emigrants and quota refugees took German language courses to prepare for university studies in Germany. The not always friendly reception of this group of people in my new homeland - we sometimes had to deal with xenophobic attacks or window stickers with slogans like "Foreigners out" - reminded me that I had once been a foreigner myself. In Congo I learned and experienced that we are all human beings.

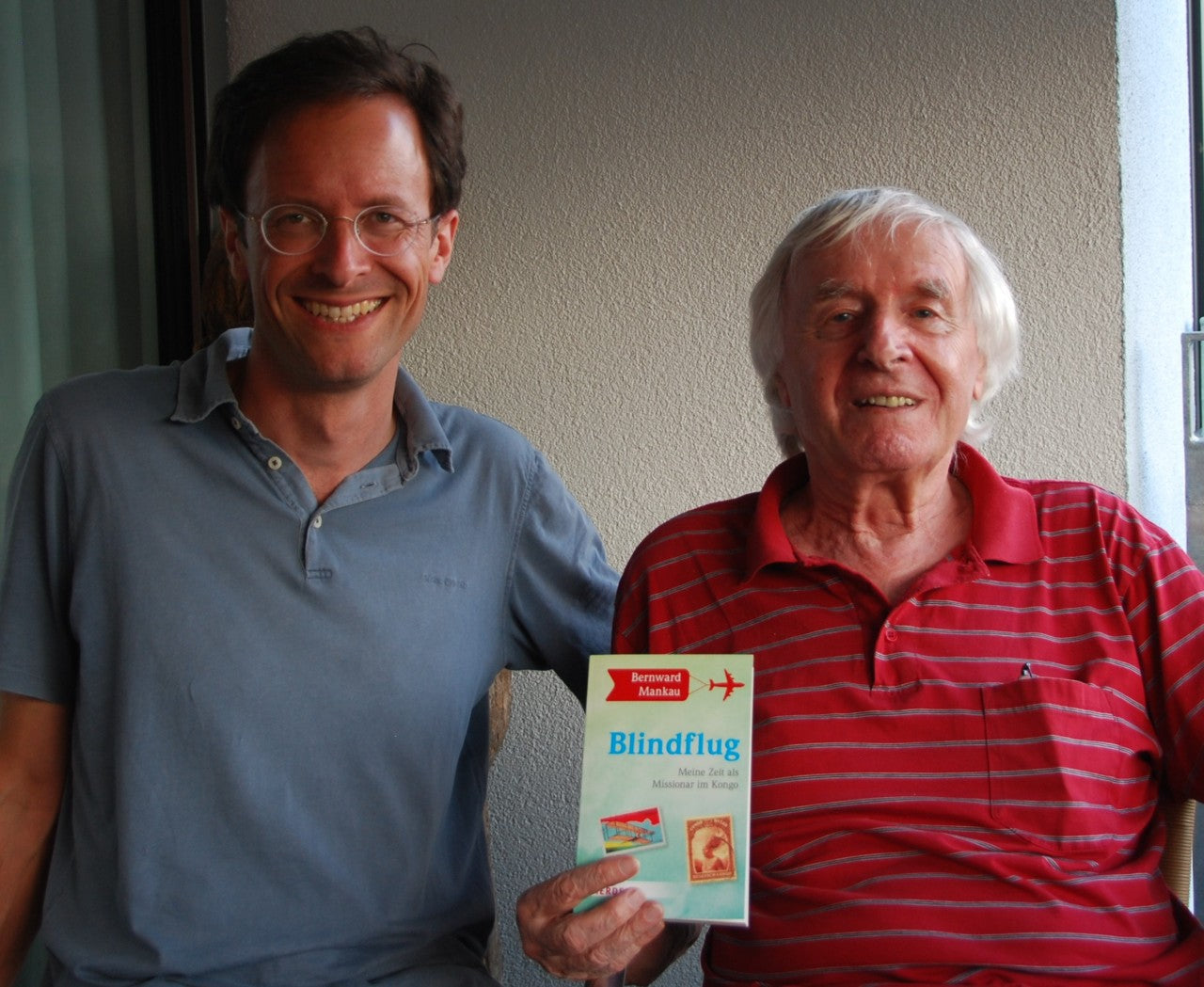

About the author:

Bernward Mankau (born 1937) graduated from the Josephinum high school in Hildesheim and studied philosophy and theology in St. Augustin. He went to Paris and Lyon to study French and completed his tertiary studies in Rome. In 1964 he flew to the Congo for the first time for a short time and experienced the great upheavals in Africa; he stayed there for a total of six years. After his time in the Congo, he was head of the education center in Murnau am Staffelsee. Extensive travels took him repeatedly to Africa and Southeast Asia.

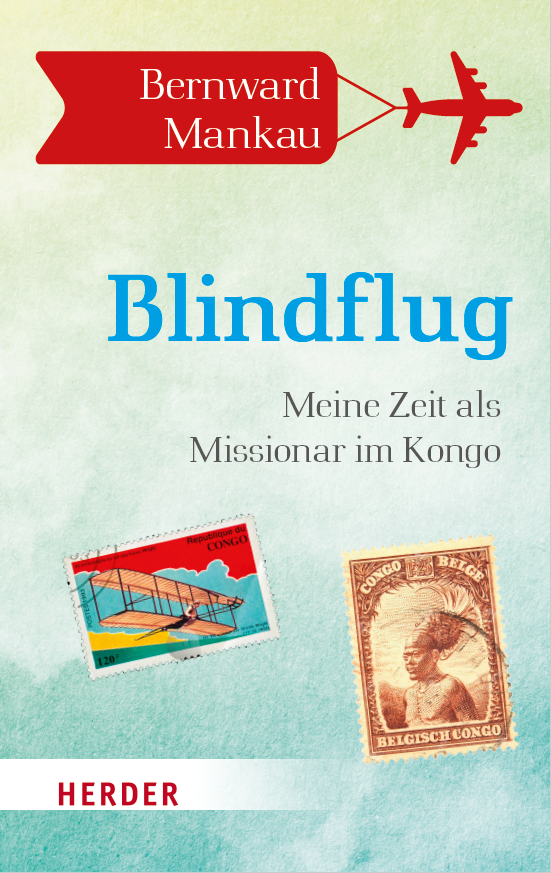

Book tip:

Bernward Mankau: Blind Flight. My time as a missionary in the Congo. Herder Publishing House, 1st edition 2020, paperback, 207 pages,

14.00 euros (D) / 14.40 euros (A), ISBN 978-3-451-03271-4

Link recommendations:

About the book "Blind Flight. My time as a missionary in the Congo", Herder Publishing

More about Bernward Mankau

To the reading sample